A colossal catfish believed to cause earthquakes beneath the earth.

It represents seismic calamity, ground-bound power, and divine punishment.

Primary Sources

Classical & Mythological Records

Edo period namazu-e earthquake lore and seismic deity traditions

Earthquake spirit and ground-shaking monster folktales

大鯰・地震神・地霊怪異に関する江戸期説話資料

Modern Folklore References

Yanagita Kunio — earthquake yōkai beliefs

Komatsu Kazuhiko — yōkai of seismic calamity

Ōnamazu – The Giant Catfish Beneath Japan

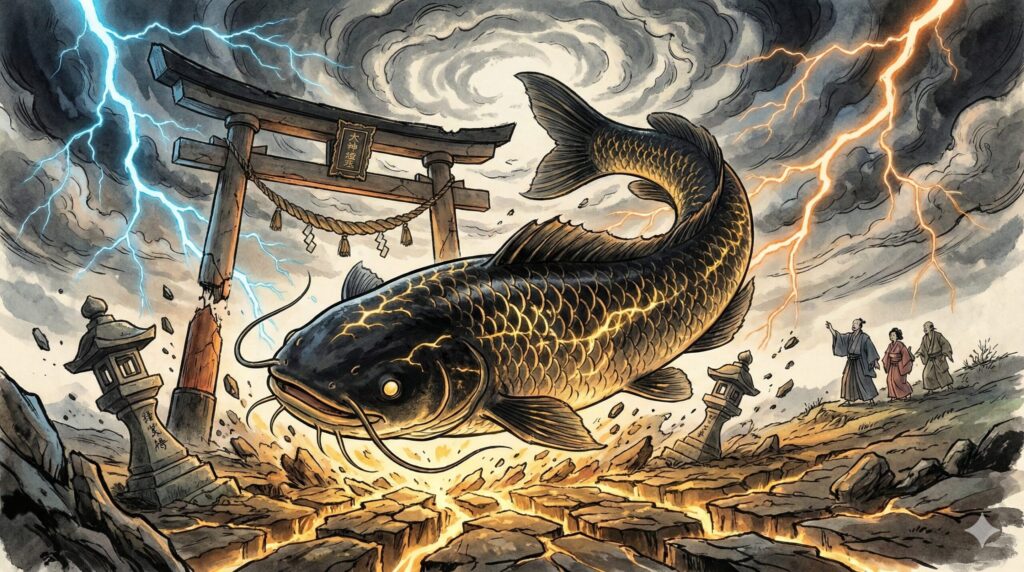

Ōnamazu (大鯰) is one of the most powerful and enduring figures in Japanese mythology — a colossal catfish said to dwell deep beneath the earth, whose violent thrashing causes earthquakes across the land. Dwelling in the dark underworld waters that support the islands, Ōnamazu embodies both the fertile and destructive aspects of nature itself: a creature of chaos, renewal, and trembling balance.

Unlike many folkloric beings tied to mountains or forests, Ōnamazu belongs to the hidden realm beneath — the unseen foundation of the Japanese archipelago. Revered, feared, and placated through centuries, this vast subterranean spirit serves as both destroyer and restorer, a mythic explanation for the unpredictable forces that shape the islands.

Origins and Mythic Context

The earliest references to Ōnamazu appear in Edo-period accounts linking earthquakes to divine punishment or imbalance within the world. However, the roots of the myth likely stretch far earlier, drawing from animistic Shinto beliefs in the spirits of the earth and water.

According to tradition, Ōnamazu lies deep underground beneath the Japanese islands, restrained by the god Kashima with a massive stone known as the Kaname-ishi (要石, “keystone”). When Kashima’s attention wavers, the giant catfish stirs — its movements shaking the land and unleashing devastating tremors. This simple yet potent story gave symbolic form to Japan’s ever-present relationship with seismic instability.

The myth also reflects the human attempt to personify and control nature’s most frightening unpredictability. By turning the earthquake into the restless twitch of a living being, the story of Ōnamazu transformed terror into ritual, chaos into meaning.

From Chaos Bringer to Symbol of Renewal

While Ōnamazu began as a creature of destruction, later interpretations reframed it as a bringer of necessary change. In Edo-period prints and popular beliefs, earthquakes — though tragic — were sometimes seen as cleansing forces that toppled corrupt elites and reset stagnant societies.

In namazu-e woodblock prints, the catfish appears with a wry, almost human face, sometimes apologetic, sometimes mischievous, surrounded by people alternately cursing or thanking it. These depictions emerged after the great Ansei Earthquake of 1855, when social commentary and folk spirituality merged.

In this sense, Ōnamazu came to represent not only nature’s wrath but also its capacity for balance and renewal — an unsettling but essential reminder that the earth beneath civilization is alive, sentient, and impartial.

Symbolism and Themes

The Unseen Power Beneath

Ōnamazu’s domain is the unseen, the abyss below the surface where forces of creation and destruction intertwine. Its immense body coils beneath the islands, invisible yet omnipresent — a metaphor for the hidden currents that sustain life but can, at any moment, overturn it.

Instability and Divine Restraint

The image of the god Kashima pressing down the catfish with the Kaname-ishi encapsulates the delicate balance between chaos and order. The world’s stability depends on divine vigilance; when that vigilance falters, the boundary breaks. This reflects a deeply Japanese sensibility — harmony not as permanence, but as tension continually maintained.

Punishment and Purification

In Buddhist and folk interpretations alike, earthquakes caused by Ōnamazu could signify karmic retribution or cleansing. The catfish’s movement punishes human arrogance, greed, and imbalance, yet through destruction comes purification and renewal — echoing cyclic themes found throughout Japanese cosmology.

Related Concepts

Watatsumi (海神)

Sea deities.

→ Watatsumi

Aramitama (荒御魂)

Violent divine aspects.

→ Aramitama

Chinkon (鎮魂)

Ritual pacification.

Marebito (稀人)

Otherworldly visitors.

→ Marebito

Depictions and Iconography

Ōnamazu’s image varies across eras. In early art, it is an enormous, dark-scaled catfish with luminous eyes, its whiskers curling like waves. During the Edo period, it took on anthropomorphic features, smiling or frowning amid crowds of townspeople. In modern depictions, it often emerges from fractured ground, illuminated by molten light or moonlit water, a colossal embodiment of seismic energy.

Folk artists portrayed Ōnamazu as both deity and scapegoat — a symbol of collective anxiety and resilience. The namazu-e prints sometimes showed priests or deities striking or pacifying the fish, while ordinary citizens cheered, prayed, or scolded it. These images reveal how myth, humor, and moral reflection intertwined in times of disaster.

Regional Variations and Cultural Resonance

Different regions of Japan developed unique legends surrounding the great catfish. In Kashima (Ibaraki Prefecture), shrines dedicated to the god who restrains Ōnamazu still stand, their stones said to suppress the beast below. Other areas preserve tales of tremors caused by smaller “namazu spirits,” each governing local earth or river domains.

The motif of the subterranean catfish also connects to agricultural fertility myths: after an earthquake, the soil becomes richer, the fields renewed. Thus, Ōnamazu embodies not merely destruction but transformation — upheaval as prelude to growth.

Modern Cultural Interpretations

This blade symbolizes seismic calamity and ground-bound punishment.

It visualizes earth-shaking power condensed into weapon form.

In modern Japan, Ōnamazu has transcended folklore to become a cultural symbol of resilience and environmental awareness. Its image appears in manga, anime, and disaster-prevention campaigns as a mascot or cautionary spirit, blending fear and familiarity.

Artists reimagine the catfish as a guardian of balance — an ancient consciousness watching humanity’s fragile constructions from beneath. Others portray it in abstract or metaphorical form, as tectonic pulse, memory of the sea, or embodiment of nature’s living will.

In some modern visual reinterpretations, Ōnamazu manifests as a yōtō — a blade whose core bears ripple-like seismic lines. The sword seems to hum faintly, embodying pressure held beneath apparent calm.

Through all reinterpretations, the essence remains: stability is an illusion resting atop a sentient, shifting world.

Modern Reinterpretation – Ōnamazu as the Earth That Is Not Still

Ōnamazu does not shake the world. It allows the world to move.

The “beautiful girl” form does not symbolize nature. She does not warn. She does not protect.

Her silent presence represents stability that never truly existed — ground that only appears firm because it has not yet shifted.

She does not threaten. She does not promise. She does not judge.

In this visual form, Ōnamazu becomes a contemporary yokai of latent motion — a spirit that exists only while the earth has not yet decided to move.

Musical Correspondence

The accompanying track translates subterranean pressure into sound. Low sustained drones, slow tectonic pulses, and distant percussive echoes evoke motion trapped beneath stillness.

Silence acts not as calm, but as compression — framing sound as tension waiting for release.

Together, image and sound form a unified reinterpretation layer — a modern folklore artifact of a world that is never truly still.

She embodies seismic force and subterranean wrath.

Her presence reflects earth-bound calamity made visible.