Tennyo – Celestial Maidens Between Heaven and Earth in Japanese Folklore

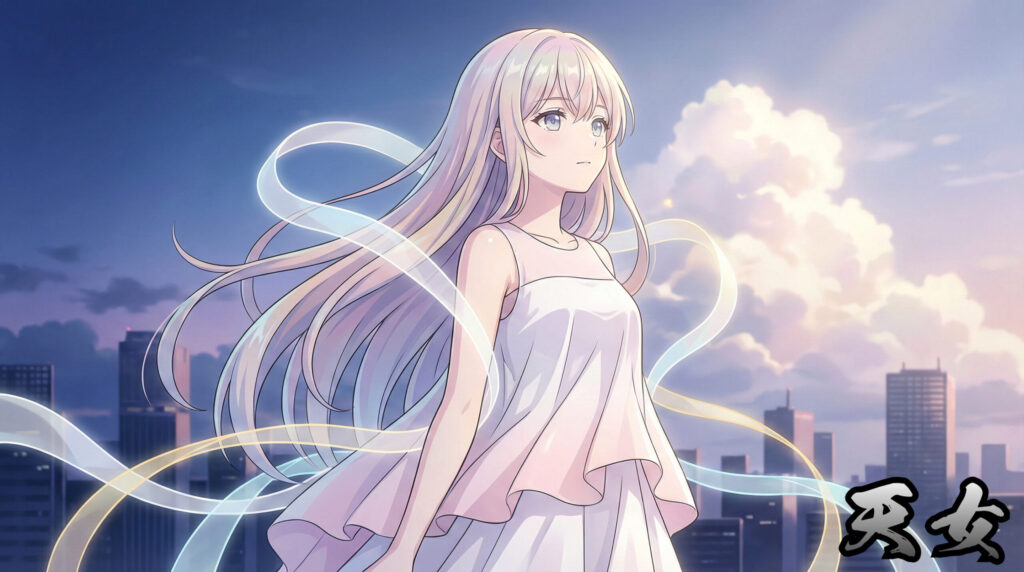

Tennyo are among the most graceful and melancholic figures in Japanese folklore: celestial maidens who descend from the heavens to the human world, often bathing in secluded lakes or rivers. Neither yōkai nor mortal, tennyo embody beauty, purity, and separation—beings whose presence brings wonder, yet whose fate is defined by impermanence.

Unlike monsters that intrude violently, tennyo arrive silently. Their stories are not driven by fear, but by longing. When a human encounters a tennyo, the meeting is fleeting, marked by awe and inevitability. The human world can never fully contain them.

Tennyo represent the sorrow that arises when heaven and earth briefly touch—and must part.

Origins and Cultural Background

The tennyo legend has roots in Buddhist cosmology, particularly the apsaras of Indian and Chinese tradition—heavenly dancers who serve the gods. Through cultural transmission, this image entered Japan and merged with local folktales, producing uniquely Japanese narratives centered on loss and separation.

By the medieval period, tennyo stories had spread widely across regions, each adapting the motif to local geography. Lakes, mountains, and forests became sites of descent, grounding celestial myth in familiar landscapes.

Unlike doctrinal figures, tennyo are shaped by oral storytelling, poetry, and performance, making them emotionally resonant rather than theologically rigid.

Appearance and the Hagoromo

Tennyo are typically described with restrained elegance:

Ethereal beauty without excess ornament

Flowing robes that shimmer like clouds or water

A serene, distant expression

The hagoromo—feathered robe or celestial mantle

The hagoromo is central to tennyo lore. It is not merely clothing, but the means by which the tennyo return to heaven. Without it, they are trapped on earth, bound to human time and limitation.

This garment becomes the axis of many tales—hidden, stolen, or withheld—transforming beauty into captivity.

The Descent and Human Encounter

Most tennyo legends follow a similar structure. A tennyo descends to bathe. A human—often a fisherman, woodcutter, or farmer—discovers her and takes the hagoromo. Deprived of her robe, the tennyo cannot return to heaven and remains in the human world.

In some versions, she becomes a wife and bears children. In others, she lives quietly, longing for the sky. Eventually, the hagoromo is returned or rediscovered, and the tennyo ascends, leaving behind family, memory, and silence.

The human gains wonder, then loss. The tennyo regains freedom, at the cost of attachment.

Love Without Permanence

A defining feature of tennyo stories is the imbalance of desire. Humans cling; tennyo endure. Even when love is genuine, it cannot overcome the fundamental divide between worlds.

The tennyo’s departure is rarely framed as betrayal. It is necessity. Heaven calls not out of cruelty, but because it is where she belongs.

This framing shifts the tragedy away from moral failure and toward existential incompatibility.

Symbolism and Themes

Beauty as Impermanence

Tennyo embody beauty that cannot be possessed or preserved.

The Cost of Desire

Human longing leads to temporary closeness, followed by inevitable loss.

Separation of Worlds

Heaven and earth touch only briefly, then part.

Freedom Over Attachment

Return to the sky represents restoration, not abandonment.

Regional Variations and Performance

Tennyo legends appear throughout Japan, most famously in the Hagoromo legend associated with Miho no Matsubara. These stories became foundational material for Noh theater, where slow movement, restrained emotion, and poetic language emphasize distance and inevitability.

In performance, the tennyo is often portrayed as both radiant and sorrowful—already aware that the encounter will end.

This performative tradition cemented the tennyo as symbols of fleeting grace rather than narrative resolution.

Modern Interpretations

In modern media, tennyo are often romanticized as angelic figures or idealized feminine forms. Some interpretations soften the sorrow, emphasizing fantasy over loss.

However, traditional power lies in restraint. Tennyo are compelling not because they stay, but because they leave. Their stories resist happy endings, favoring quiet departure over resolution.

They remain symbols of beauty remembered, not retained.

Conclusion – Tennyo as Emblems of Fleeting Grace

Tennyo are not figures of punishment or reward. They are reminders. Their descent illuminates the human world briefly, and their ascent restores the order of realms.

Through their stories, Japanese folklore articulates a profound truth: some encounters are meaningful precisely because they cannot last.

The tennyo does not belong to earth—and that is why her presence matters.

Music Inspired by Tennyo (Celestial Maiden)

Music inspired by tennyo often emphasizes lightness, suspension, and gentle sorrow. Slow, flowing melodies and airy textures can evoke drifting clouds and quiet descent.

Instruments with long decay—strings, flutes, soft pads—mirror the feeling of movement without weight. Melodies may rise gradually and then fade, echoing the ascent back to heaven.

By focusing on grace, distance, and impermanence, music inspired by tennyo captures their essence: a fleeting harmony between worlds, beautiful precisely because it cannot remain.