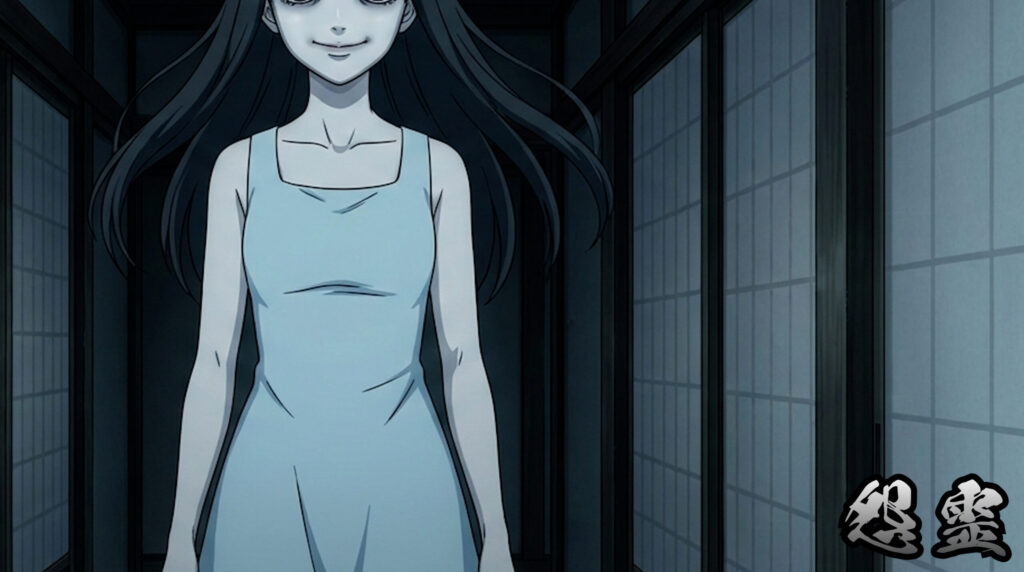

A vengeful human spirit formed through injustice and unresolved death.

It represents calamity, curse, and political fear.

Primary Sources

Classical & Mythological Records

Heian period court onryō chronicles and calamity records

Setsuwa collections describing vengeful noble spirits

御霊信仰・怨霊鎮魂に関する中世宮廷記録

Modern Folklore References

Yanagita Kunio — studies on goryō / onryō beliefs

Komatsu Kazuhiko — vengeful spirit and curse transformation lore

Onryō – Reframing the Concept of Vengeful Spirits in Japanese Folklore

Onryō(怨霊) is not a single supernatural being, but a genre-defining concept within Japanese folklore and religious imagination. The term refers to spirits born from powerful resentment, yet its meaning extends far beyond “vengeful ghost.” Onryō function as a framework for understanding how emotion, social injustice, and spiritual imbalance are believed to manifest after death.

Rather than asking what an onryō looks like, Japanese tradition asks why an onryō comes into being. This causal orientation distinguishes onryō from many other supernatural categories and makes the concept central to the structure of Japanese ghost belief as a whole.

The Core Definition of Onryō

At its most basic level, an onryō is a spirit generated by unresolved grievance (怨). However, the grievance itself is not sufficient. Onryō emerge when resentment:

- Is socially unacknowledged

- Cannot be resolved within existing power structures

- Persists beyond death without ritual release

In this sense, onryō are not aberrations but systemic responses—spiritual consequences of imbalance rather than individual monstrosities.

Historical Formation of the Onryō Concept

Court Society and Political Fear

The onryō concept crystallized during periods when political conflict, exile, and unjust death were common among elites. Misfortune—plagues, disasters, sudden deaths—was often interpreted as the work of resentful spirits of wronged individuals.

This interpretation reframed catastrophe as moral consequence, not random event. Appeasement, rather than destruction, became the logical response.

From Individual Spirit to Structural Category

Over time, onryō ceased to be tied exclusively to named historical figures. The concept expanded to include anonymous spirits whose grievances mirrored broader social tensions, allowing onryō to become a general explanatory model.

Onryō Versus Other Supernatural Categories

Clarifying the onryō concept requires distinguishing it from related forms.

- Yūrei are defined by lingering attachment, not necessarily resentment

- Ikiryō originate from living consciousness rather than postmortem fixation

- Muen-botoke arise from abandonment rather than grievance

Onryō are unique in that emotion itself is the engine of manifestation. Without resentment, the category collapses.

Emotion as Supernatural Force

One of the most distinctive features of the onryō framework is its treatment of emotion as causally potent. Anger, humiliation, and despair are not internal states alone; when suppressed or ignored, they acquire agency.

This belief aligns with broader Japanese folk logic, in which imbalance—rather than evil—produces danger. The onryō is not wicked by nature; it is reactive.

Ritual Response and Pacification

Unlike monsters that must be defeated, onryō must be recognized and appeased. Historical responses include:

- Memorial rites

- Posthumous restoration of honor

- Deification or enshrinement

These acts do not erase resentment but transform it, converting destructive force into protective or neutral presence. The boundary between onryō and kami is therefore porous, not absolute.

Symbolism and Cultural Meaning

Social Critique Through the Supernatural

Onryō narratives allow critique of injustice without direct confrontation. Blame is displaced onto the supernatural, while responsibility remains implicitly human.

Fear of Suppressed Voices

Onryō embody anxiety over what happens when voices are silenced. Their return insists that unresolved wrongs do not simply disappear.

Order Through Acknowledgment

The onryō framework asserts that stability requires acknowledgment of harm. Ignoring grievance invites catastrophe; recognition restores balance.

Related Concepts

Goryō (御霊)

Pacified vengeful spirits.

→ Goryō

Ikiryō (生霊)

Living spirit projections.

→ Ikiryō

Aramitama (荒御魂)

Violent divine aspects.

→ Aramitama

Chinkon (鎮魂)

Ritual pacification.

Modern Cultural Interpretations

This blade symbolizes unresolved injustice and political curse.

It visualizes human resentment condensed into weapon form.

In modern culture, onryō are often reduced to horror archetypes — figures of indiscriminate violence. This simplification obscures the original logic of the concept.

Contemporary reinterpretations that restore causality — linking manifestation to social pressure, trauma, or injustice — align more closely with traditional understanding.

In some modern visual reinterpretations, onryō manifest as a yōtō — a blade forged from accumulated grievance. The sword does not strike randomly; it responds, turning cause into consequence.

Onryō remain relevant because the conditions that create them persist.

Modern Reinterpretation – Onryō as a System, Not a Monster

In contemporary analysis, Onryō—traditionally understood as spirits of unresolved grievance—are often flattened into symbols of chaos and revenge. Yet the true depth of the concept lies not in horror, but in structure. The onryō does not arise arbitrarily; it manifests where moral, emotional, or social imbalance has reached a breaking point. It is the logic of consequence made visible.

Modern reinterpretations that reintroduce causality—connecting haunting to injustice, repression, or systemic neglect—restore the philosophical coherence of the original folklore. Within this framework, the onryō becomes less a supernatural aggressor and more a mechanism of reckoning. It enforces equilibrium where human institutions fail. The haunting is not random—it is procedural.

In visual reinterpretations, this principle takes form through the yōtō known as the “Grievance Blade.” Its steel is forged not from ore but from repetition: every injustice folded into its edge until the metal remembers. When it moves, it does so in silence—its cut is not wrath, but judgment. The sword’s aura hums faintly, as if recording both the cause and its echo. In this way, the onryō is not a vengeful apparition, but a living record of imbalance made manifest.

This perspective transforms fear into recognition. The Onryō becomes the cultural mechanism by which the unseen—pain, repression, forgotten wrong—demands articulation. It is less a being than a feedback loop: a social, spiritual, and psychological system that ensures what was buried will eventually surface. The onryō does not choose to appear; it is summoned by omission.

Musical Correspondence

Music inspired by Onryō explores the architecture of tension and release, mirroring the process of resentment coalescing into presence. Gradual layers of drone, sustained strings, and subharmonic textures accumulate like compressed emotion beneath ritual restraint. Each repetition deepens pressure until sound itself feels inhabited.

When rupture comes, it is abrupt but not chaotic—a transition from suppression to inevitability. Percussive strikes or distorted reverberations may signify emotional breach, yet resolution never arrives cleanly. Instead, tones decay into uneasy quiet, suggesting appeasement rather than victory.

Through this progression, compositions inspired by Onryō reflect the cyclical nature of grievance: silence giving rise to sound, consequence following neglect, and equilibrium restored only through recognition. The result is not music of vengeance, but of moral resonance—a haunting that fulfills its purpose and then withdraws.

She embodies lingering resentment and political memory.

Her presence reflects injustice made visible.