A shrine maiden possessed by fox spirits through ritual or misfortune.

It represents possession, liminality, and divine interference.

Primary Sources

Classical & Mythological Records

Nihon Shoki (日本書紀)

Bizen Fudoki (備前国風土記)

Kibi region mythological traditions

Modern Folklore References

Yanagita Kunio — Kibi demon folklore

Komatsu Kazuhiko — Yōkai Encyclopedia

Kitsunetsuki no Miko – The Shrine Maiden Between Divine Will and Possession in Japanese Folklore

Kitsunetsuki no Miko, the “Fox-Possessed Shrine Maiden,” is a figure that exists at the intersection of faith, fear, and ambiguity in Japanese folklore. She is neither purely victim nor purely medium—neither wholly sacred nor entirely cursed. Through her, the fox spirit speaks, acts, and distorts.

Unlike wandering yōkai or deliberate ritual curses, fox possession unfolds within religious space. The shrine, meant to protect and purify, becomes the stage for uncertainty. Is the voice divine guidance, or invasive spirit?

Kitsunetsuki no Miko embodies belief under pressure.

Origins in Fox Possession Belief

Belief in kitsunetsuki (fox possession) has existed for centuries across Japan, particularly in rural communities. Fox spirits were thought to enter humans—often women—causing strange speech, appetite changes, convulsions, or prophetic utterances.

When such possession occurred in or around shrines, the afflicted woman might be identified as a miko. This created tension: miko were expected to channel divine voices, yet fox spirits were not always trusted as benevolent.

The fox blurred the boundary between kami and yōkai.

The Shrine Maiden as Vessel

Miko traditionally serve as intermediaries between humans and the divine. This role requires openness—ritual purity, receptivity, and emotional sensitivity.

These same qualities make them vulnerable to possession. In folklore, the fox does not always force entry; it slips in where the boundary is thin.

Thus, the kitsunetsuki no miko is not seized—she is inhabited.

Appearance and Signs of Possession

Descriptions of fox-possessed shrine maidens emphasize subtle disruption:

Eyes reflecting animal sharpness

Speech shifting between human and inhuman tones

Sudden knowledge or prophecy

Uncontrolled laughter or hunger

Movements that feel rehearsed yet wrong

Physically, she may remain outwardly composed. The unease lies in inconsistency—moments when the voice no longer matches the body.

The fox does not hide. It blends.

Divine Message or Deception

One of the central tensions surrounding kitsunetsuki no miko is interpretation. Some communities believed fox spirits could act as messengers of Inari, conveying warnings or blessings. Others viewed them as tricksters, corrupting sacred space.

This ambiguity is never fully resolved. The same utterance might be taken as prophecy or delusion depending on outcome.

Faith becomes unstable.

Social Consequence and Isolation

Fox possession carried stigma. A woman believed to be possessed could be feared, avoided, or expelled. Even shrine maidens were not exempt.

In some tales, the miko is revered briefly, then abandoned once the fox’s presence becomes inconvenient. In others, exorcism restores her—but leaves lasting distance.

Possession reshapes social identity.

Symbolism and Themes

Boundary Between Kami and Yōkai

The sacred is not always pure.

Voice Without Ownership

Who speaks through the body?

Female Mediation and Vulnerability

Openness invites power and risk.

Faith as Uncertainty

Belief requires interpretation.

Related Concepts

Kitsune (狐)

Fox spirits.

→ Kitsune

Ikiryō (生霊)

Living spirit projections.

→ Ikiryō

Miko (巫女)

Shamanic priestesses.

→ Miko

Aramitama (荒御魂)

Violent divine aspects.

→ Aramitama

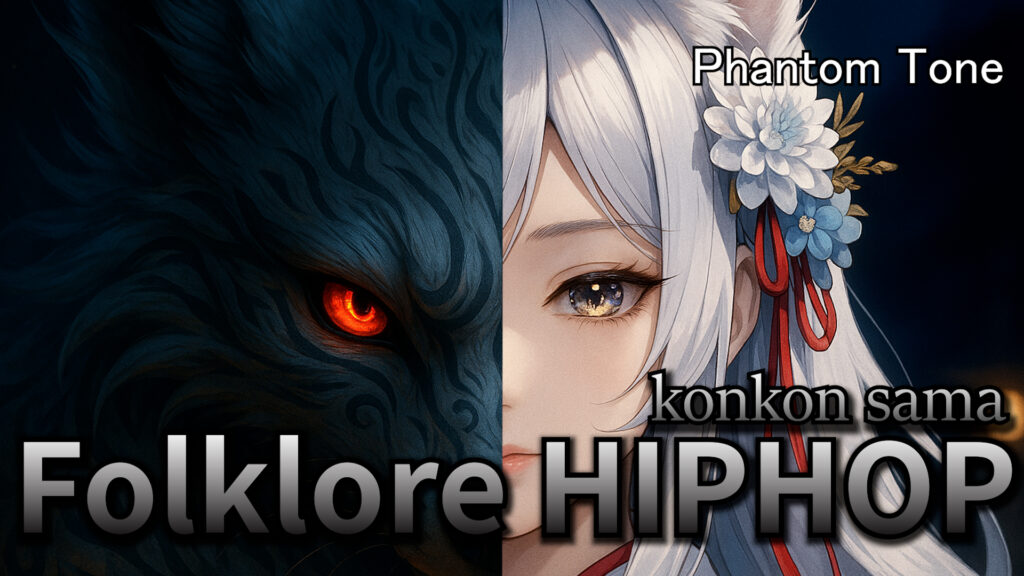

Kitsunetsuki no Miko in Folklore and Art

Fox-possessed shrine maidens appear in folktales, ethnographic records, and later fiction as figures of quiet tension. Visual depictions often emphasize contrast: pure shrine garments paired with fox shadows, tails, or eyes reflected in darkness.

The fox is rarely shown fully. Its presence is implied.

The body becomes contested ground.

Modern Cultural Interpretations

This blade symbolizes spirit possession and ritual boundary collapse.

It visualizes divine interference condensed into weapon form.

In modern readings, kitsunetsuki no miko is often interpreted through psychological and sociological lenses — dissociation, hysteria, trauma, and the burden of religious expectation.

Contemporary fiction and art may reclaim her as a figure of hybrid identity — one who embodies belief and doubt, control and surrender.

In some modern visual reinterpretations, kitsunetsuki no miko manifests as a yōtō — a blade engraved with ritual seals. The sword trembles between command and possession, embodying voice without autonomy.

Her relevance persists because questions of voice and agency remain unresolved.

Modern Reinterpretation – Kitsunetsuki no Miko as the Vessel Who Cannot Be Certain

In modern interpretation, Kitsunetsuki no Miko—the fox-possessed shrine maiden—embodies one of folklore’s most profound ambiguities: the instability of voice. No longer viewed merely as a case of possession or moral corruption, she is now read as a site of collision between faith, psychology, and power. Contemporary scholars and artists interpret her as a mirror for dissociation, religious ecstasy, and social confinement—a person who becomes sacred precisely because she loses control.

In this modern frame, the maiden is both subject and instrument: her voice amplified yet questioned, her body sanctified yet surveilled. Within ritual contexts, she is a conduit for divinity; within modern analysis, she becomes a text of resistance and breakdown. Her state of possession reflects the friction between individual agency and communal expectation—between the right to feel and the duty to conform.

In visual reinterpretations, the yōtō that represents her condition is known as the “Whispering Seal Blade.” Its steel is etched with countless inverted ofuda, and when unsheathed, the talismanic script hums faintly—as if something within is trying to speak. The sword does not obey its wielder outright; it hesitates, stutters, and at times seems to move of its own accord. Its edge represents speech without certainty, the act of utterance detached from authority.

Through this lens, Kitsunetsuki no Miko becomes more than a story of possession; she is an allegory for the self under duress—split between belief and disbelief, service and survival. She asks questions that have no exorcism: when does faith become surrender? When does inspiration become intrusion? Her silence is not absence; it is negotiation.

Musical Correspondence

Music inspired by Kitsunetsuki no Miko occupies a liminal soundscape between ritual and rupture. Traditional instruments such as koto, shō, and taiko may form a ceremonial base, only to be destabilized by irregular rhythms, reversed samples, or whispered vocal textures. Each element mirrors her unstable possession—harmony disturbed by subtle interference.

Layered chanting or echo effects can simulate dialogue between two presences inhabiting the same sonic body. Minor tonalities intertwined with sudden bursts of brightness evoke moments when divinity and hysteria become indistinguishable. The music’s structure resists resolution, hovering between trance and release.

Through this auditory tension, compositions inspired by Kitsunetsuki no Miko capture

She embodies possession and ritual liminality.

Her presence reflects divine interference made visible.