A mischievous child-like tree spirit of Okinawa, associated with banyan trees.

It represents trickery, fertility, and local guardian belief.

Primary Sources

Classical & Mythological Records

Nihon Shoki (日本書紀)

Bizen Fudoki (備前国風土記)

Kibi region mythological traditions

Modern Folklore References

Yanagita Kunio — Kibi demon folklore

Komatsu Kazuhiko — Yōkai Encyclopedia

Kijimunā – Forest Child Spirits of Okinawan Folklore

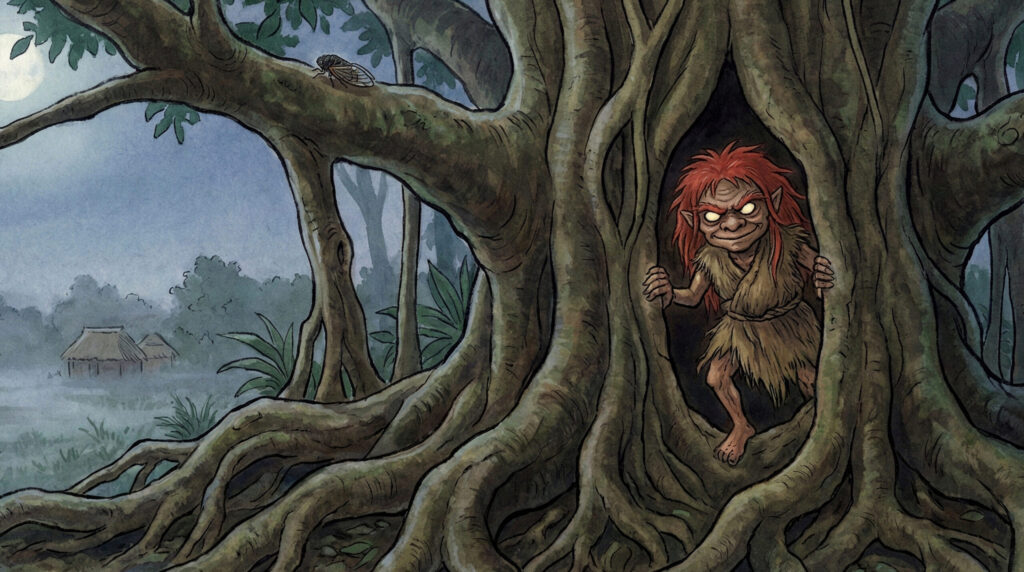

Kijimunā are distinctive spirit beings from Okinawan folklore, closely associated with ancient banyan trees (gajumaru) and the subtropical forests of the Ryukyu Islands. Often described as child-sized figures with red hair and playful expressions, kijimunā occupy a unique position between yōkai, nature spirits, and local deities.

Unlike fear-driven monsters or moral enforcers, kijimunā are primarily tricksters. They laugh, tease, and disrupt, but rarely with lasting harm. Their presence reflects a worldview shaped by close coexistence with nature—where spirits are not distant abstractions, but neighbors sharing the same land.

Rooted deeply in Okinawan environment and culture, kijimunā embody regional identity as much as supernatural belief.

Origins and Regional Context

Kijimunā belong specifically to the folklore of Okinawa and the former Ryukyu Kingdom, rather than mainland Japan. Their legends emerged from a subtropical landscape rich in dense forests, coastal villages, and sacred trees. Among these, the gajumaru tree holds special significance, often believed to serve as a dwelling place for spirits.

Early accounts portray kijimunā as forest-dwelling beings who occasionally interact with humans—especially fishermen, farmers, and children. They are not associated with formal religious doctrine, but with oral tradition, local customs, and everyday life.

This regional grounding sets kijimunā apart from many pan-Japanese yōkai. They are spirits of place, inseparable from the land itself.

Appearance and Characteristics

Descriptions of kijimunā are relatively consistent across stories:

Small, childlike stature

Bright red or reddish-brown hair

Mischievous facial expressions

Barefoot or lightly clothed

Often associated with trees, rivers, or beaches

In some tales, kijimunā resemble human children closely enough to be mistaken at a distance. Their otherness is revealed through behavior rather than monstrous features.

They are agile, quick to laugh, and fond of jokes—sometimes harmless, sometimes inconvenient.

Behavior and Human Encounters

Kijimunā are known for playful but disruptive behavior. Common stories describe them:

Stealing fish or tools and returning them later

Messing with fishing nets or boats

Laughing loudly when surprising humans

Playing with children near forests or shores

While they may cause trouble, kijimunā rarely inflict serious harm. However, angering them—by disrespecting nature or mocking them—can lead to ongoing mischief or bad luck.

Interestingly, many legends emphasize mutual respect. Humans who treat kijimunā kindly may receive help or protection in return.

Relationship with Nature

Kijimunā are inseparable from the natural environment. Their connection to gajumaru trees reflects broader Okinawan beliefs about sacred landscapes and spiritual presence in nature.

Rather than dominating or judging humans, kijimunā coexist alongside them. They react to human behavior toward the environment, reinforcing a reciprocal relationship rather than a moral hierarchy.

This ecological closeness gives kijimunā a gentler tone than many mainland yōkai, aligning them more closely with nature spirits than demons.

Symbolism and Themes

Playfulness and Disorder

Kijimunā represent chaos that is lighthearted rather than destructive.

Childhood and Wildness

Their childlike form reflects freedom, curiosity, and emotional immediacy.

Respect for Nature

They embody the consequences—positive or negative—of how humans treat their environment.

Regional Identity

Kijimunā symbolize Okinawan cultural distinctiveness within Japanese folklore.

Related Concepts

Kappa (河童)

Water-associated trickster yokai.

→Kappa

Marebito (稀人)

Otherworldly visitors.

→Marebito

Tree Spirits (木霊 / Kodama)

Forest-dwelling spiritual beings.

→Kodama

Ancestral Spirits (祖霊)

Local guardian presences.

Kijimunā in Folktales and Local Memory

Kijimunā appear primarily in oral stories passed down through generations. Unlike courtly myths or Buddhist tales, their stories are grounded in village life, fishing routines, and forest paths.

Encounters are often personal and anecdotal rather than epic. Someone laughs at night and later realizes a kijimunā was nearby. A fisherman finds his catch disturbed but senses no malice.

These small-scale stories reinforce kijimunā as familiar presences rather than distant legends.

Modern Cultural Interpretations

This blade symbolizes arboreal trickery and territorial guardianship.

It visualizes forest-bound mischief turned into weapon form.

In modern Okinawa, kijimunā often appear as friendly mascots, children’s book characters, and symbols of regional heritage. Their image has been softened, emphasizing charm and friendliness over mischief.

Despite this, traditional stories preserve their unpredictability. They are not pets or decorations — they remain spirits deserving of respect.

Contemporary interpretations increasingly frame kijimunā as icons of environmental harmony and cultural preservation.

In some modern visual reinterpretations, kijimunā manifest as a yōtō — a blade grown from coral-red wood. The sword embodies balance between playfulness and boundary, reminding its bearer that harmony requires respect.

Kijimunā endure because harmony still needs guardians.

Modern Reinterpretation – Kijimunā as Spirits of Playful Coexistence

In this modern reinterpretation, Kijimunā emerge not merely as folk creatures of the Ryukyu Islands, but as enduring emblems of environmental harmony and cultural continuity. Their modern depictions — on murals, mascots, and tourism symbols — transform mischief into charm, yet their essence remains untamed. Beneath their red hair and wide eyes lies the same playful unpredictability that once startled fishermen and travelers beneath the banyan trees.

The “beautiful guardian” visualization reimagines Kijimunā as luminous beings of coral and wood, their small bodies glowing softly with sunset tones. Their hair resembles flowing seaweed tinged in ember light, their eyes reflecting ripples of tide pools at dusk. Around them, leaves and tiny fish seem to orbit in quiet rhythm — a suggestion that nature itself bends gently to their play. Their smiles carry both invitation and warning: joy offered freely, yet never without consequence.

The yōtō born from their world is no weapon of war, but a coral-wood blade that seems to breathe with salt and wind. Its surface bears living grain — patterns that shimmer like sunlit waves. When drawn, the sword hums softly, releasing faint motes of light that drift like seafoam. It exists not to cut, but to remind: boundaries keep balance, and respect sustains harmony. To wield it carelessly is to fracture the very laughter it protects.

Through this vision, Kijimunā embody the philosophy that coexistence is not absence of conflict, but the art of gentle negotiation. They teach that reverence for nature can be joyful rather than solemn, mischievous rather than moralistic. In a time when harmony is too often framed as silence, the Kijimunā whisper that laughter — wild, unpredictable, and kind — is its truest expression.

Musical Correspondence

The corresponding composition translates the forest’s pulse into sound. Wooden percussion evokes roots striking the earth, while soft marimba and plucked strings create the sensation of footsteps darting between branches. Layers of rhythmic dialogue emerge — playful, teasing, and alive.

Occasional bursts of flute or bell-like tones mimic sudden appearances and vanishing gestures. The harmony never settles completely; it sways, like tide and breeze in quiet argument. Between patterns, silence lingers — not emptiness, but anticipation.

By weaving together rhythm, texture, and mischief, the music captures Kijimunā’s essence: guardianship without solemnity, joy with consequence, and the laughter of a world that remembers how to live alongside wonder.

She embodies woodland mischief and territorial spirit.

Her presence reflects local guardian trickery made visible.