Demonic beings associated with punishment, disaster, and boundary violation.

They represent chaos restrained by ritual order.

Primary Sources

Classical and Religious Records

- Nihon Shoki (日本書紀)

- Konjaku Monogatari-shū (今昔物語集)

- Temple chronicles and Setsubun ritual traditions

Modern Folklore References

- Yanagita Kunio — Oni belief studies

- Komatsu Kazuhiko — Yōkai Encyclopedia

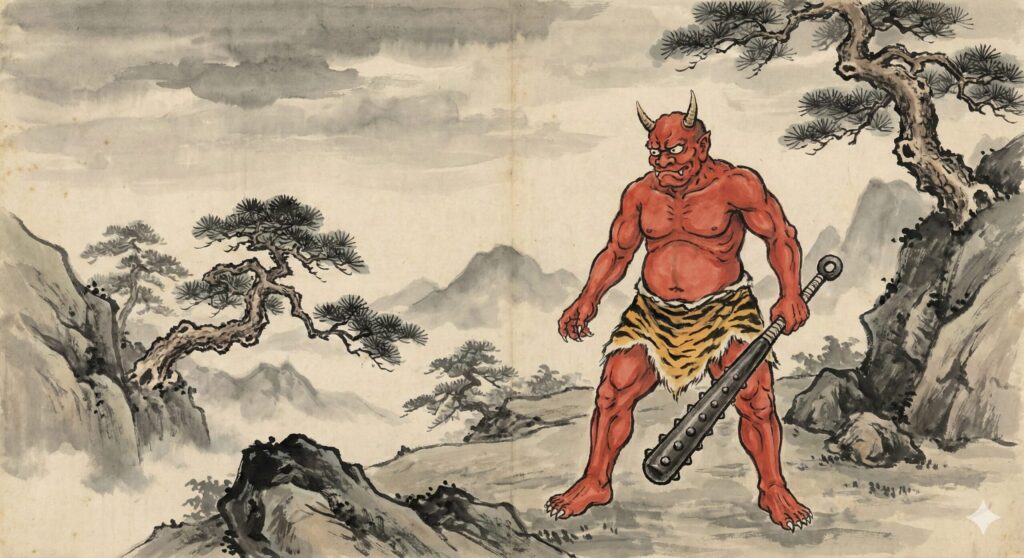

What Are Oni?

Oni (鬼) are among the most iconic and feared figures in Japanese folklore. Often portrayed as large, muscular beings with wild hair, sharp claws, and brightly colored skin, they typically possess one or two horns and carry iron clubs known as kanabō. Their image is deeply rooted in ancient ritual beliefs, Buddhist cosmology, and stories of chaotic forces that threaten the natural order.

Historically, Oni served as representations of calamity, disease, and moral corruption. Rather than being a single species of monster, the term Oni functioned as a broad category for malevolent, supernatural presences—spirits that bring misfortune, punish the wicked, or roam between worlds. Over centuries, their depiction shifted from invisible forces to the heavily stylized horned demons seen in classical art.

Origins and Historical Development

The earliest roots of Oni can be found in indigenous Japanese concepts of invisible, harmful presences known as mono or magatsuhi. Later, with the introduction of Buddhism, Oni absorbed characteristics of gaki (hungry ghosts) and hellish wardens, creating a hybrid image that symbolized both earthly danger and spiritual punishment.

Throughout the Heian and medieval periods, Oni appear frequently in literature such as Konjaku Monogatari and various emaki (picture scrolls). They serve as antagonists, embodiments of human vices, or manifestations of profound emotional turmoil. Their imagery became particularly standardized during the Edo period, where artists emphasized bright colors, exaggerated horns, and dramatic physical features that continue to define Oni today.

Symbolic Roles of Oni

Despite their terrifying appearance, Oni occupy complex symbolic roles:

- Agents of Punishment: Oni often serve as executors of karmic justice, punishing those who commit immoral acts.

- Embodiments of Chaos: They represent natural disasters, epidemics, and forces beyond human control.

- Manifestations of Inner Darkness: In literature and Noh drama, Oni frequently symbolize overwhelming emotions such as jealousy, grief, or rage.

- Ritual Protectors: Ironically, Oni masks are used in festivals such as Setsubun to drive away evil, demonstrating their dual nature as both threat and protection.

Related Concepts

Aka-oni & Ao-oni

Moral contrast oni.

→Aka-oni & Ao-oni

Kishin (鬼神)

Divine oni spirits.

→Kishin

Shuten Dōji (酒呑童子)

Legendary oni leader.

→Shuten Dōji

Aramitama (荒御魂)

Violent divine aspects.

→Aramitama

Oni in Art and Cultural Imagery

Edo-period artists played a pivotal role in cementing the modern visual identity of Oni. Works by Toriyama Sekien and other painters expanded their mythology, portraying Oni as tragic, comedic, or grotesque figures. Their visual boldness—vivid skin tones, oversized weapons, and dynamic postures—has influenced everything from classical theater to modern animation, games, and global fantasy design.

Modern Interpretations of Oni

This blade symbolizes unrestrained calamity and sacred punishment.

It visualizes chaos given ritual form.

In modern reinterpretations, Oni are increasingly depicted not merely as monsters or moral antagonists, but as concentrated embodiments of destructive authority — figures whose violence is no longer chaotic, but ritualized, justified, and systematized. In visual reinterpretation frameworks, Oni are sometimes reimagined as yōtō (cursed blades) — weapons that do not symbolize personal hatred, but institutional punishment. These blades are not carried by heroes; they are issued by systems. They exist to enforce order through fear, representing violence that is accepted because it is considered “necessary.” Within this transformation, Oni shift from “beings that break the rules” to mechanisms that enforce them. The blade does not scream. It judges. Oni endure because societies always preserve a shape for sanctioned destruction.

Modern Reinterpretation – Oni as the Mirror of Human Power

In modern reinterpretation, Oni transcend their historical role as embodiments of evil or punishment. They have become reflections of human intensity — figures that externalize the emotions, desires, and impulses too overwhelming to contain. Within them, rage becomes sacred, and sorrow becomes strength. The Oni no longer stands apart from humanity; it stands for everything humanity suppresses.

The “beautiful girl” visualization channels this duality with haunting grace. Her appearance fuses elegance with volatility — horns curving like molten metal, eyes gleaming between sorrow and defiance. Crimson threads lace her kimono, shifting like veins of living flame. She does not roar or strike; her power is poised, patient, and undeniable — a storm paused at the edge of release.

In her hand, the yōtō glows with restrained fury. The blade hums softly, its edge marked by faint pulse-like patterns, as if the weapon breathes. It is both instrument and burden — a symbol of power that must be carried rather than unleashed. Around her, the air trembles with invisible pressure, echoing the mythic tension between divine wrath and human restraint.

Through this reinterpretation, Oni becomes the embodiment of intensity without apology — not villain, not savior, but presence. She is the spirit of uncontainable emotion rendered visible: beauty that threatens, rage that mourns, and strength that remembers what it once protected.

Musical Correspondence

The accompanying composition translates this balance between ferocity and grace into sound. Deep percussion establishes ritual gravity, while layered taiko rhythms simulate the heartbeat of something ancient waking beneath restraint. Distorted bass tones and metallic overtones convey the sonic texture of raw energy contained.

Midway, a choral motif emerges — distant, sorrowful, almost human — only to dissolve into rhythmic pulse once more. The piece swells but never detonates; its climax is tension itself. Every sound seems on the verge of collapse, yet the collapse never comes.

Through this structure, the music captures Oni’s enduring paradox: chaos made sacred, fury made beautiful. It is not the sound of destruction, but of power refusing to be simplified — the eternal rhythm of what humanity fears, reveres, and carries within.

She embodies disaster and ritualized violence.

Her presence reflects chaos restrained by tradition.