A colossal centipede yokai dwelling in mountains and ruins.

It represents calamity, poison, and devouring disaster.

Primary Sources

Classical and Medieval Records

- Ōeyama Engi (大江山縁起)

- Konjaku Monogatari-shū (今昔物語集)

- Regional mountain folklore of giant centipede spirits

Modern Folklore References

- Yanagita Kunio — Mountain spirit studies

- Komatsu Kazuhiko — Yōkai Encyclopedia

Ōmukade – Colossal Centipedes of Japanese Folklore

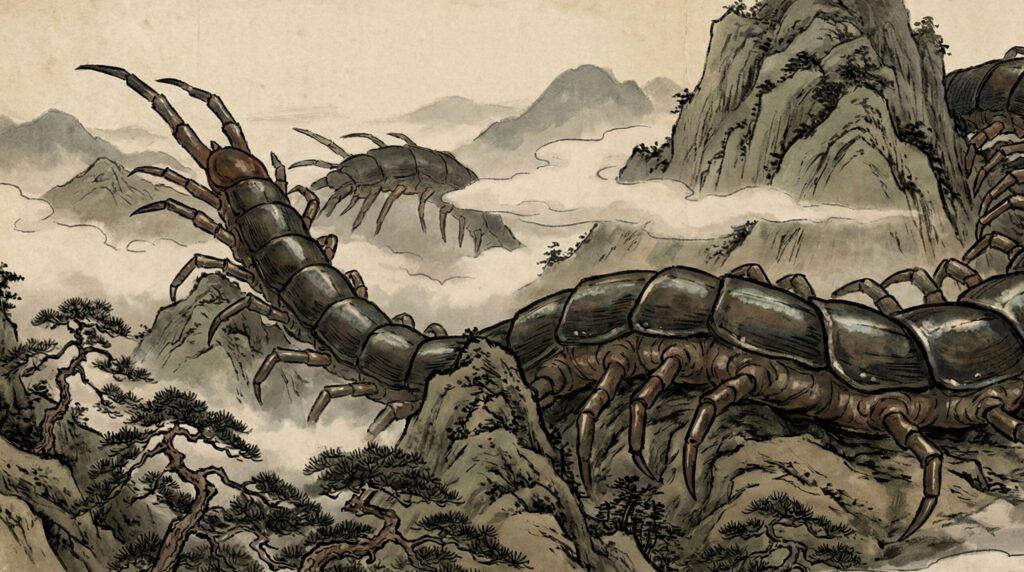

Ōmukade are among the most fearsome and viscerally unsettling creatures in Japanese folklore: gigantic centipedes whose size, venom, and relentless movement inspire deep dread. Unlike tricksters or ambiguous spirits, ōmukade represent overwhelming menace—creatures that crawl, coil, and advance without hesitation.

Often associated with mountains, caves, and remote regions, ōmukade are not merely enlarged insects. They are embodiments of unchecked aggression, territorial dominance, and the terror of nature magnified beyond human scale. Their many legs, armored bodies, and poisonous bite transform a familiar creature into something profoundly alien.

In folklore, the appearance of an ōmukade signals not mischief or moral testing, but direct existential threat.

Origins and Early Accounts

Legends of giant centipedes appear in early Japanese chronicles and regional folklore, especially in mountainous areas. One of the most famous tales involves the warrior Fujiwara no Hidesato (Tawara Tōda), who slays a colossal centipede that had been terrorizing a dragon palace beneath Lake Biwa.

In these stories, the ōmukade often inhabits cliffs, peaks, or deep caverns, emerging to prey upon animals, humans, or even dragons. Its scale defies ordinary combat, requiring heroic intervention or divine assistance.

These narratives reflect ancient fears of the wild—regions beyond cultivation where human order collapses and monstrous life thrives.

Appearance and Physical Terror

Descriptions of ōmukade emphasize excess and repetition:

Enormous length, stretching across valleys or wrapping around mountains

Countless armored segments and legs

Venomous fangs capable of killing instantly

Relentless, crawling movement without pause

Unlike serpents or dragons, which may possess elegance or intelligence, ōmukade are often portrayed as purely instinctual. Their terror lies in persistence rather than cunning. They advance, bite, and constrict without mercy.

This insectile inhumanity amplifies fear, removing any possibility of negotiation or understanding.

Enemies of Dragons and Gods

A notable feature of ōmukade lore is their antagonism toward dragons. In several legends, centipedes attack or threaten dragon deities, forcing divine beings to seek human help.

This inversion—where a lowly insect becomes the enemy of celestial beings—heightens the sense of unnatural imbalance. The ōmukade is not just dangerous; it violates the cosmic hierarchy.

Only exceptional heroes, armed with skill, courage, and often sacred weapons, can defeat such a creature. Victory restores balance between human, natural, and divine realms.

Symbol of Mountain Terror

Mountains in Japanese folklore are places of both sanctity and danger. Ōmukade embody the hostile aspect of these landscapes—steep cliffs, hidden crevices, and poisonous life.

Their association with mountains reinforces themes of isolation and escalation. Far from villages and protection, humans confront a force that dwarfs them physically and spiritually.

The centipede’s venom adds another layer of fear: not just death, but suffering and corruption of the body.

Symbolism and Themes

Overwhelming Nature

Ōmukade represent nature unchecked by human order or ritual.

Inhuman Persistence

Their endless legs and crawling motion symbolize relentless threat.

Cosmic Imbalance

Their conflict with dragons reflects disruption of the natural hierarchy.

Heroic Restoration

Their defeat reaffirms human courage aligned with divine order.

Related Concepts

Yato-gami (夜刀神)

Serpent-like mountain deities.

→Yato-gami

Nozuchi (野槌)

Ground serpent spirits.

→Nozuchi

Aramitama (荒御魂)

Violent divine aspects.

→Aramitama

Kama-itachi (鎌鼬)

Mountain wind spirits.

→Kama-itachi

Ōmukade in Art and Folklore

In illustrated scrolls and later prints, ōmukade are often depicted coiling around mountains or looming over warriors. Artists emphasize scale, repetition, and texture—rows of legs, layered armor, and shadowed segments.

Unlike humorous yōkai, ōmukade imagery is uncompromising. There is little exaggeration for comedy; the intent is to inspire awe and fear.

These images cemented the centipede as one of the most physically terrifying beings in Japanese myth.

Modern Cultural Interpretations

This blade symbolizes creeping calamity and consuming disaster.

It visualizes silent approach and inevitable ruin.

In modern media, ōmukade often appear as boss monsters, ancient evils, or symbols of primordial fear. Games and anime emphasize their size, venom, and unstoppable movement, translating folkloric terror into spectacle.

Despite modernization, the core theme remains unchanged: the fear of being overwhelmed by something that cannot be reasoned with.

In some modern visual reinterpretations, ōmukade manifest as a yōtō — a blade segmented like an armored body. The sword’s ridged spine echoes crawling multiplicity, embodying motion that never stops.

Ōmukade endure because primal discomfort with crawling multiplicity and poison still resonates.

Modern Reinterpretation – Ōmukade as the Relentless Force Beneath

In this modern vision, Ōmukade is no longer just a monstrous insect — it is the embodiment of inevitability. Its terror does not arise from intent or malice, but from motion that cannot stop, hunger that cannot think, and persistence that outlasts resistance. It represents not evil, but scale: a life-form too vast and alien to coexist with human rhythm.

The “beautiful girl” visualization transposes this primal horror into something eerily elegant. Her hair spills like segmented armor, each strand glinting with metallic sheen. Bands of crimson and black coil around her arms and legs, recalling the rhythmic pattern of centipede legs in endless motion. Her gaze is steady, predatory, yet strangely detached — as if curiosity has replaced cruelty.

The yōtō she holds mirrors the creature’s structure: its spine segmented, its blade alive with a faint iridescence that ripples down its length like motion trapped in metal. Each ridge hums with restrained vibration, suggesting energy waiting to uncoil. Behind her, the air bends as though the world itself is retreating from her gravity.

Through this reinterpretation, Ōmukade becomes a symbol of inhuman persistence — the will that survives simply by continuing. It is not the predator that kills for need, but the embodiment of accumulation, of progress without empathy. The beautiful girl’s stillness contrasts the implied movement within her, turning dread into poise, and monstrosity into endurance.

Musical Correspondence

The accompanying track transforms endless motion into sound. Heavy, syncopated percussion creates a pulse that never resolves, layered with low mechanical rhythms mimicking a thousand synchronized limbs. Metallic scraping and distorted bass lines evoke both movement and suffocation.

Midway, the tempo fractures — percussion shifts unpredictably, but the rhythm never halts. Tension builds without climax; each repetition tightens the atmosphere like coiling armor. Moments of silence feel like breath held before the next crawl resumes.

By focusing on unstoppable motion and claustrophobic density, the music mirrors Ōmukade’s essence: terror born from continuity. It is not a chase, but a realization — that something vast, ancient, and unfeeling is already in motion beneath you, and it will not stop.

She embodies creeping calamity and toxic persistence.

Her presence reflects destruction that advances quietly.