What Are Oni?

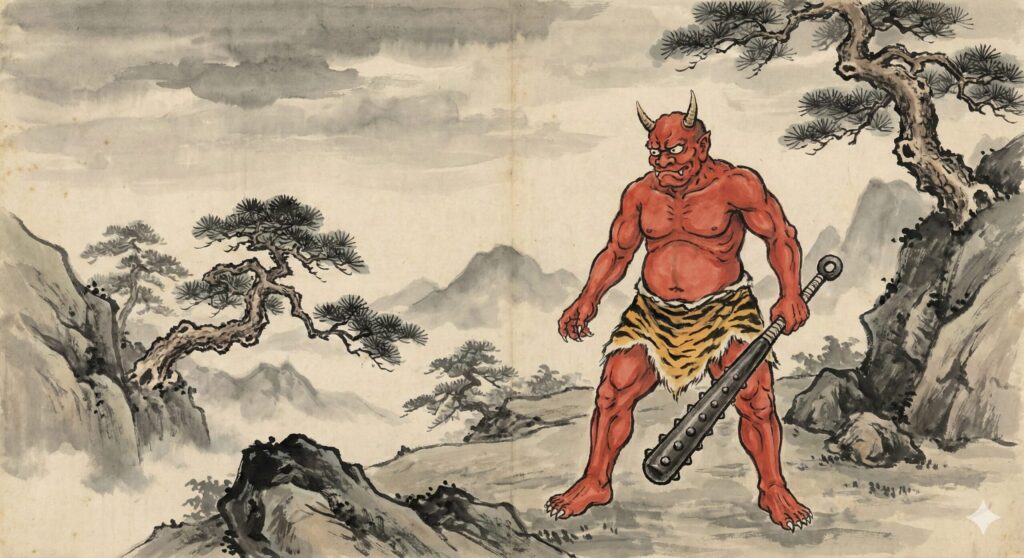

Oni (鬼) are among the most iconic and feared figures in Japanese folklore. Often portrayed as large, muscular beings with wild hair, sharp claws, and brightly colored skin, they typically possess one or two horns and carry iron clubs known as kanabō. Their image is deeply rooted in ancient ritual beliefs, Buddhist cosmology, and stories of chaotic forces that threaten the natural order.

Historically, Oni served as representations of calamity, disease, and moral corruption. Rather than being a single species of monster, the term Oni functioned as a broad category for malevolent, supernatural presences—spirits that bring misfortune, punish the wicked, or roam between worlds. Over centuries, their depiction shifted from invisible forces to the heavily stylized horned demons seen in classical art.

Origins and Historical Development

The earliest roots of Oni can be found in indigenous Japanese concepts of invisible, harmful presences known as mono or magatsuhi. Later, with the introduction of Buddhism, Oni absorbed characteristics of gaki (hungry ghosts) and hellish wardens, creating a hybrid image that symbolized both earthly danger and spiritual punishment.

Throughout the Heian and medieval periods, Oni appear frequently in literature such as Konjaku Monogatari and various emaki (picture scrolls). They serve as antagonists, embodiments of human vices, or manifestations of profound emotional turmoil. Their imagery became particularly standardized during the Edo period, where artists emphasized bright colors, exaggerated horns, and dramatic physical features that continue to define Oni today.

Symbolic Roles of Oni

Despite their terrifying appearance, Oni occupy complex symbolic roles:

- Agents of Punishment: Oni often serve as executors of karmic justice, punishing those who commit immoral acts.

- Embodiments of Chaos: They represent natural disasters, epidemics, and forces beyond human control.

- Manifestations of Inner Darkness: In literature and Noh drama, Oni frequently symbolize overwhelming emotions such as jealousy, grief, or rage.

- Ritual Protectors: Ironically, Oni masks are used in festivals such as Setsubun to drive away evil, demonstrating their dual nature as both threat and protection.

Oni in Art and Cultural Imagery

Edo-period artists played a pivotal role in cementing the modern visual identity of Oni. Works by Toriyama Sekien and other painters expanded their mythology, portraying Oni as tragic, comedic, or grotesque figures. Their visual boldness—vivid skin tones, oversized weapons, and dynamic postures—has influenced everything from classical theater to modern animation, games, and global fantasy design.

Modern Interpretations of Oni

In contemporary media, Oni have evolved into versatile characters. They may appear as monstrous antagonists, misunderstood beings shaped by sorrow, or supernatural guardians who balance destructive power with moral duty. Their symbolic flexibility allows Oni to adapt to various genres—horror, fantasy, historical epics, and even comedic storytelling.

As a cultural icon, Oni continue to embody both fear and fascination, reflecting timeless human struggles with anger, temptation, and the unknown. Their imagery remains one of the most recognizable elements of Japanese folklore worldwide.

Music Inspired by Oni

These tracks reinterpret the fierce and symbolic presence of Oni through rhythm, atmosphere, and modern storytelling. Drawing from themes of inner turmoil, supernatural power, and ritual energy, each work offers a contemporary perspective on one of Japan’s most enduring folkloric figures. The music explores both the destructive force and emotional depth associated with Oni, echoing the tension between chaos and order found throughout their mythology.