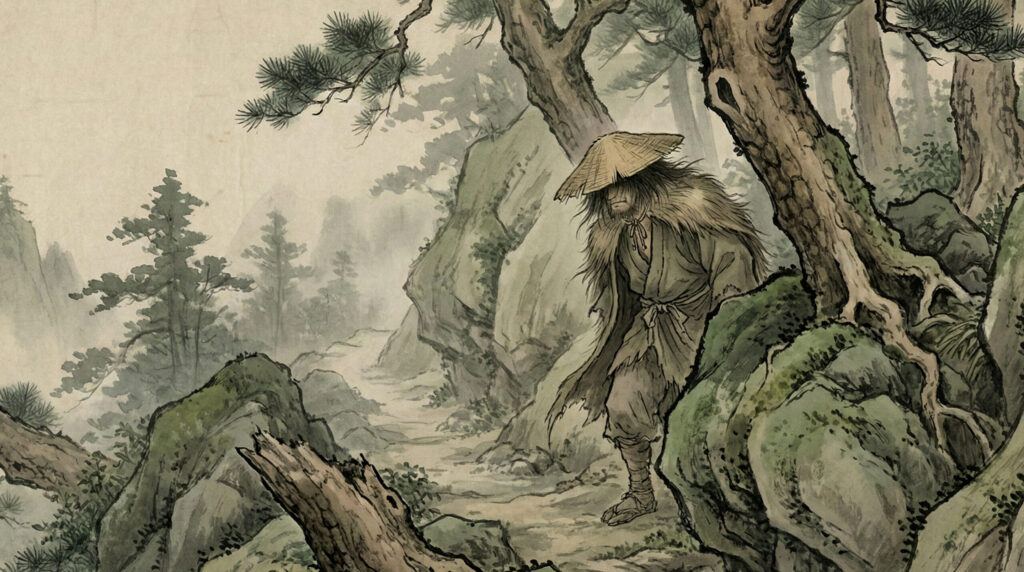

A childlike apparition wandering deep mountains.

It lures travelers from safe paths.

Primary Sources

Mountain Child Apparition Records

- Yanagita Kunio — Mountain child spirit belief studies

- Komatsu Kazuhiko — Yōkai Encyclopedia

- Regional mountain village oral traditions

Yamako – Working Spirits of the Mountain in Japanese Folklore

Yamako(山子) are lesser-known mountain beings found in regional Japanese folklore, distinct from better-known figures such as Yamawarawa (山童) or Yama-uba (山姥). Rather than representing fearsome wilderness or maternal monstrosity, yamako are understood as “working entities of the mountain”—beings associated with labor, routine activity, and the unseen functioning of mountainous spaces.

They are not defined by terror or moral judgment, but by function. Yamako appear in traditions that treat the mountain not merely as a sacred or dangerous realm, but as a place of continuous, unseen work.

Regional Origins and Folk Context

References to yamako are highly localized, appearing primarily in mountain villages where forestry, charcoal-making, hunting, or mountain agriculture shaped daily life. Unlike widely systematized yokai, yamako rarely appear in national compilations and instead survive through oral transmission and local terminology.

The term “yamako” itself suggests a subordinate or small-scale presence—neither deity nor demon, but something closer to an occupational spirit, bound to specific mountains and tasks.

This localization indicates that yamako were not abstract mythic figures, but interpretive tools used by communities to explain the rhythms and uncertainties of mountain labor.

Yamako as “Working Anomalies”

Yamako are best described as functional anomalies rather than personalities. Folklore attributes to them actions such as:

- Moving tools or materials overnight

- Completing or disrupting repetitive tasks

- Producing unexplained sounds of labor—chopping, scraping, carrying

These actions are not framed as malicious. In many accounts, yamako are neutral or even helpful, provided humans respect certain unspoken boundaries.

The idea of a mountain that “works” on its own reflects a worldview in which nature is not passive. Yamako embody this concept: the mountain as an active system rather than a silent backdrop.

Distinction from Related Mountain Beings

Yamako are often mistakenly conflated with other mountain-related figures, but important distinctions exist.

- Yamawarawa (山童) are childlike spirits, often playful or mischievous.

- Yama-uba (山姥) represent ambivalence between nurturing and devouring aspects of the mountain.

- Yamako, by contrast, are defined neither by age nor by maternal symbolism.

Their defining trait is labor without narrative. They do not teach lessons, seduce travelers, or punish arrogance. They simply act.

Symbolism and Cultural Meaning

The Mountain as a Working Entity

Yamako express a belief that the mountain itself performs labor—maintaining paths, shifting materials, and regulating resources. Human work is therefore not solitary, but entangled with unseen processes.

Respect Without Worship

Unlike gods, yamako are not worshipped. Unlike yokai, they are not feared. They occupy a middle ground where respect replaces ritual, reflecting a pragmatic relationship with nature.

Invisible Contribution

Yamako symbolize labor that goes unnoticed. Their presence acknowledges that not all work is visible, credited, or understood—an idea deeply resonant in subsistence-based communities.

Related Concepts

Child Apparition Motif

Childlike mountain spirits.

Mountain Liminal Yōkai

Beings of deep forest thresholds.

Lost Child Folklore

Spirits of vanished mountain children.

Regional Variations and Transmission

Descriptions of yamako vary by region, but consistency appears in their lack of visual detail. They are more often heard than seen, inferred from results rather than appearances.

This absence of fixed imagery suggests that yamako were never meant to be personified strongly. They function as explanatory placeholders rather than characters.

Modern Cultural Interpretations

This blade symbolizes lost guidance and fatal misdirection.

It visualizes paths that lead away from return.

In contemporary reinterpretations, yamako are sometimes framed as personifications of natural systems, spirits of maintenance and repetition, or symbols of unseen labor in modern society.

While such readings are modern, they align closely with the original concept of yamako as beings defined by what they do rather than who they are.

In some modern visual reinterpretations, yamako manifest as a yōtō — a blade shaped by repetition. The sword bears the marks of routine motion, its edge sharpened not by intent but by continual use.

Yamako persist because unseen labor still sustains visible worlds.

Modern Reinterpretation – Yamako as the Spirit of Unseen Continuity

In this reinterpretation, the yamako is not a servant or creature of burden, but the quiet embodiment of process — the rhythm that sustains without acknowledgment. It is the presence that keeps the world running while remaining unseen.

The “beautiful girl” form expresses this balance of anonymity and grace. Her movements are methodical yet fluid, every gesture repeating with unspoken precision. The marks along her blade-like silhouette suggest labor made sacred — the poetry of repetition itself.

She does not seek recognition. Her purpose exists in continuation. Around her, time feels circular: each breath, each step, each motion blending into the next, forming a serenity born of constancy rather than change.

She embodies the beauty of persistence — the idea that endurance itself can be divine. To see her is to glimpse the invisible hands that maintain the shape of the world.

In this visual reinterpretation, the yamako becomes the spirit of unseen continuity — beauty defined by repetition, and existence justified by the quiet perfection of doing what must be done.

Musical Correspondence

The accompanying track translates steady motion into sound. Soft, repeating percussive loops and restrained tonal progressions evoke rhythm as ritual — labor transformed into pulse.

Minimal melodic change reinforces continuity, while subtle textures shift just enough to remind the listener that persistence is itself alive. The piece breathes through its patterns, finding meaning not in climax but in constancy.

Through repetition, subtle evolution, and quiet balance, the music captures the yamako’s essence: a spirit that endures through function — the unseen rhythm that keeps the visible world moving.

She embodies false guidance and quiet disappearance.

Her presence marks paths that never return.