Tengu – Mountain Spirits of Japanese Folklore

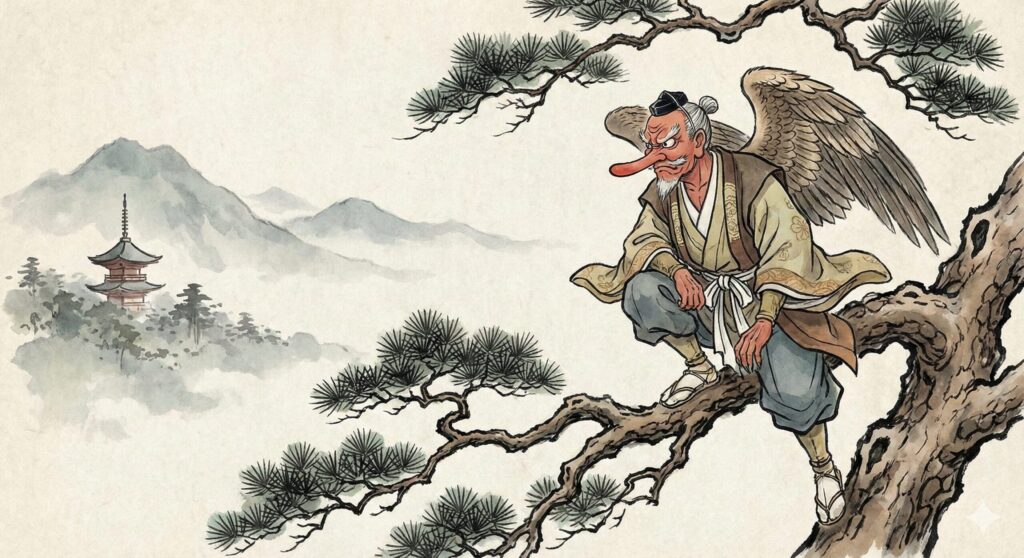

Tengu are one of the most distinctive and enduring figures in Japanese folklore: supernatural beings associated with mountains, forests, violent winds, and a fierce sense of pride. Often depicted with a red face and an unnaturally long nose, or as bird-like humanoids with wings and beaks, tengu stand at the boundary between gods, demons, and spirits. They can be tricksters, teachers, destroyers, or protectors, depending on the era, region, and story.

Over the centuries, tengu have shifted from terrifying demons of disruption to complex mountain spirits and even semi-divine guardians of sacred places. Their image blends elements of kami (Shinto deities), Buddhist demonology, and the austere life of mountain ascetics known as yamabushi. This layered history makes tengu a powerful symbol of ambiguity, liminality, and raw natural force in Japanese culture.

Origins and Early Depictions

The word tengu (天狗) is believed to have entered Japan through Chinese sources, where it originally referred to a celestial dog or comet-like apparition. In Japan, however, the concept quickly diverged from its Chinese roots and merged with local ideas about mountain spirits and disruptive forces of nature. Early Japanese texts describe tengu as ominous beings that descend from the sky, cause confusion, and mislead monks or travelers.

In medieval literature, tengu are often portrayed as enemies of Buddhism. They tempt or deceive monks, create illusions, or stir up arrogance and false enlightenment in practitioners. This association reflects concerns within Buddhist communities about pride, corruption, and spiritual delusion. Tengu thus functioned as both external monsters and internal warnings about ego.

From Demons to Mountain Spirits

Over time, the image of the tengu softened and diversified. While early tales emphasized their role as dangerous tempters or bringers of calamity, later stories began to show them as guardians of mountains and forests, and even as protectors of certain temples and shrines. This transformation parallels the broader integration of mountain cults, Shugendō practices, and syncretic beliefs that blended Shinto and Buddhism.

In many legends, tengu live deep in the mountains, training in martial arts, magic, and strict discipline. They are feared for their power but also respected as embodiments of wild wisdom, harsh but potentially enlightening. This dual nature — at once threatening and instructive — is a key part of their enduring appeal.

Types of Tengu

Folklore and later scholarship commonly distinguish between two major types of tengu, though depictions vary by region and period.

Daitengu – Great Tengu

Daitengu are the more human-like and powerful form. They typically appear as tall, imposing figures with:

- A bright red face

- An extremely long nose

- Sharp, piercing eyes

- Feathered wings on their back

- Traditional yamabushi-style robes and headgear

Daitengu are often portrayed as leaders or lords of the tengu, ruling over specific mountains or regions. They possess high intelligence, mastery of magical arts, and a haughty temperament.

Kotengu / Karasu Tengu – Small or Crow Tengu

Kotengu (small tengu) or karasu tengu (crow tengu) are more bird-like. They frequently have:

- A beak instead of a human nose

- Feathered bodies or avian heads

- Clawed hands and feet

- Wings that allow them to soar over mountains and valleys

These tengu can act as attendants, soldiers, or messengers for the great tengu. In some stories, they form flocks that swarm through the sky like storm clouds, bringing sudden winds or ominous weather as signs of their passage.

Tengu and Yamabushi – Ascetic Roots

One of the most distinctive aspects of tengu imagery is their connection to yamabushi, the mountain ascetics of Shugendō. Yamabushi practiced rigorous training, including fasting, meditation under icy waterfalls, and traversing dangerous mountain paths. Their goal was to gain spiritual power and insight through direct contact with harsh natural landscapes.

In Edo-period art, tengu often wear yamabushi garments: layered robes, a small box-like tokin headpiece, and carry ritual implements. This visual fusion suggests that tengu embody both the discipline and the danger of mountain practice — the potential for enlightenment, but also for pride and misused power.

Some tales describe human practitioners who become tengu after death or through excessive arrogance, while others present tengu as ancient beings who occasionally teach chosen students. The line between human ascetic and mountain spirit is deliberately blurred.

Symbolism and Themes

Arrogance and Spiritual Error

In Buddhist-influenced narratives, tengu frequently symbolize arrogance, false enlightenment, and attachment to power. A monk who becomes overly proud of their knowledge, sermons, or miracles might fall under tengu influence, losing sight of genuine compassion and humility.

Guardians of Sacred Mountains

At the same time, tengu can function as guardians of specific mountains, temples, or hidden training grounds. They drive away those who approach with greed or disrespect, but may spare or even aid those who show sincerity and courage. In this sense, tengu are gatekeepers to the numinous landscape.

Embodiments of Wind and Sky

With their wings, flight, and association with sudden gusts, tengu are closely tied to wind and sky. Stories often mention roaring winds, swirling leaves, and rapidly changing weather as signs of tengu activity. This connects them to the unpredictable, overwhelming side of nature.

Ambiguity Between Good and Evil

Unlike purely demonic entities, tengu occupy a morally ambiguous space. They can be cruel or generous, deceptive or instructive. This ambiguity reflects a broader theme in Japanese folklore: powerful beings are not neatly categorized as good or evil, but must be approached with respect and caution.

Related Concepts

Yamabushi (山伏)

Mountain ascetics associated with tengu.

Mountain Kami (山神)

Divine mountain authorities.

Ascetic Boundary Motif

Spirits testing discipline.

Tengu in Literature and Art

Tengu appear in a wide range of classical literature, from medieval war tales to humorous Edo-period anecdotes. They might kidnap children, challenge warriors, or test monks through illusions. Sometimes they are defeated; other times they simply vanish back into the mountains, leaving mystery behind.

In visual art, tengu became a favorite subject for woodblock prints and paintings. Artists depicted them:

- Soaring above pine-covered peaks

- Training swordsmen in remote clearings

- Gathering in councils atop crags

- Interacting with humans in strange, dreamlike encounters

These images shaped the modern, iconic form of the red-faced long-nosed tengu seen in masks, festivals, and contemporary media.

Regional Variations and Local Legends

Different regions of Japan developed their own tengu traditions. Certain mountains became known as tengu strongholds, associated with specific named figures. Local legends tell of:

- Travelers who got lost in sudden fog and later realized they had been led astray by tengu

- Swordsmen who gained unmatched skill after secret training with a tengu master

- Villages that both feared and relied on tengu to guard nearby forests

These regional stories add texture to the broader image of tengu as complex mountain entities woven deeply into local landscapes and histories.

Modern Cultural Interpretations

This blade symbolizes ascetic law and spiritual arrogance.

It visualizes punishment triggered by pride.

In modern culture, tengu continue to appear across manga, anime, games, novels, and visual art. They may be portrayed as villains, mentors, or enigmatic guardians, shaped by centuries of reinterpretation. Their mask-like faces and flowing robes make them instantly recognizable symbols of Japanese supernatural imagery.

Contemporary creators often emphasize the dynamic, aerial qualities of tengu — wings, command of wind, and fluid movement between mountain and sky. These attributes naturally inspire modern visual and sonic reinterpretations rooted in height, motion, and shifting perspective.

In some modern visual reinterpretations, tengu manifest as a yōtō — a blade that cuts through air before it cuts through matter. The sword rides currents of wind, its presence defined by velocity and altitude rather than weight.

Tengu persist because movement between worlds still fascinates.

Modern Reinterpretation – Tengu as the Spirit of Boundless Ascent

In this reinterpretation, the tengu is not simply a warrior or demon, but the embodiment of unrestrained motion — the will of the mountain carried by air. It exists in the instant between earth and sky, where gravity releases and perception expands.

The “beautiful girl” form expresses this through motion rather than posture. Her hair and garments flow like wind currents, her gaze distant yet commanding. Feathers trace her silhouette, hinting at form only when the light shifts — presence revealed through movement alone.

She is not bound by direction. Each gesture seems to carve the air, reshaping space as she moves. Her beauty is not stillness, but velocity — the grace of something that refuses to remain grounded.

Her existence is invitation and warning alike: ascension without humility becomes peril. Yet she remains serene, aware that balance itself is the art of flight.

In this visual reinterpretation, the tengu becomes the spirit of boundless ascent — beauty drawn from altitude, and freedom defined by the distance between sky and self.

Musical Correspondence

The accompanying track translates air into rhythm and space. Sweeping pads and sharp percussive strikes mirror the rise and fall of wings, while shifting tonal layers evoke sudden altitude changes and open sky.

Fast, rhythmic pulses blend with long reverberations, suggesting both precision and chaos — the dance between control and surrender that defines flight. The music breathes with the same instability that governs wind: never resting, always in motion.

Through contrast, height, and velocity, the composition captures the tengu’s essence — a being of proud grace, suspended between power and humility, teaching that to soar is also to risk the fall.

She embodies mountain law and spiritual trial.

Her presence tests discipline rather than mercy.