It reflects the folkloric use of visual symbolism to encode social warning rather than narrative myth.

Primary Sources

Edo-Period Illustrated Encyclopedias

- Gazu Hyakki Yagyō (画図百鬼夜行) — Toriyama Sekien

- Konjaku Hyakki Shūi (今昔百鬼拾遺) — Toriyama Sekien

Classical and Regional Folklore Records

- Local oral traditions of Kumamoto Prefecture

- Shrine and village records associated with Abura-sumashi legends

Modern Academic References

- Komatsu Kazuhiko — Yōkai Encyclopedia

- Yanagita Kunio — Tōno Monogatari

Abura-sumashi – A Yokai of Deception, Satire, and Moral Ambiguity in Japanese Folklore

Abura-sumashi(油すまし) is a yokai documented in Edo-period sources, most notably in illustrated encyclopedias of supernatural beings. Unlike purely monstrous entities, abura-sumashi exists at the intersection of folklore, social satire, and moral critique, making it a particularly layered and intellectually rich figure.

Often depicted as a strange, humanoid creature with an uncanny expression and monk-like features, abura-sumashi resists straightforward categorization. It is at once a trickster yokai, a cautionary emblem of greed, and a reflection of social tensions surrounding religious authority in early modern Japan.

Edo-Period Documentation and Visual Tradition

Abura-sumashi appears in Edo-period yokai compendia, where it is typically illustrated rather than extensively narrated. These visual records describe it as a being encountered at night, often mistaken at first for a wandering monk or ascetic.

The name “abura-sumashi” literally suggests someone who “steals oil” or “finishes oil,” a reference to lamp oil—an essential and valuable commodity in premodern daily life. The yokai is said to deceive travelers, approaching under the guise of a harmless religious figure before revealing its unsettling nature.

The scarcity of detailed narrative is itself significant. Abura-sumashi functions less as a story-driven monster and more as a conceptual warning encoded in image and name.

Oil, Theft, and Everyday Anxiety

In the Edo period, oil was indispensable. It fueled lamps, supported domestic life, and symbolized security after dark. Theft of oil was not merely petty crime; it threatened safety and stability.

Abura-sumashi embodies this anxiety. Rather than stealing valuables openly, it targets something mundane yet vital. This choice grounds the yokai firmly in everyday concerns, distinguishing it from fantastical predators or legendary demons.

The act of oil theft also carries moral weight: it is quiet, indirect, and difficult to notice—mirroring the deceptive nature attributed to abura-sumashi.

The Monk Image and Social Satire

One of the most striking aspects of abura-sumashi is its association with the image of a monk or religious ascetic. This association invites interpretation beyond simple fear.

During the Edo period, Buddhist institutions were deeply embedded in social administration. While respected, they were also subject to skepticism and satire. Abura-sumashi can be read as a folkloric expression of this ambivalence: a figure that outwardly resembles moral authority but secretly engages in unethical behavior.

Importantly, this does not represent an attack on Buddhism as doctrine, but rather a critique of hypocrisy within religious roles. The yokai becomes a mirror reflecting social distrust.

Yokai, Allegory, or Moral Emblem?

Abura-sumashi occupies an unstable position between categories.

- As a yokai, it deceives and unsettles.

- As a social allegory, it critiques greed and false piety.

- As a moral emblem, it warns against appearances divorced from conduct.

This ambiguity is not a flaw but a defining feature. Abura-sumashi demonstrates how yokai could function as vehicles for social commentary, especially in a period when direct criticism was constrained.

Symbolism and Cultural Meaning

Deception Without Violence

Abura-sumashi does not kill, curse, or attack. Its threat lies in misdirection and erosion of trust. This subtlety aligns it with anxieties about moral decay rather than physical danger.

Sacred Appearance, Profane Action

The contrast between monk-like appearance and ignoble behavior encapsulates a recurring theme in Japanese folklore: the danger of mistaking form for essence.

The Everyday as a Site of the Supernatural

By centering on lamp oil, abura-sumashi situates the supernatural squarely within ordinary life. Darkness does not fall through dramatic catastrophe, but through small, unnoticed losses.

Related Concepts

Tsukumogami (付喪神)

Objects that acquire spirit through prolonged use, closely related to everyday-object yokai and quiet household anxieties.

Marebito (稀人)

Sacred visitors from outside the community whose presence blurs trust, familiarity, and spiritual boundary.

→ Marebito Page

Household & Village Yokai

Everyday yokai rooted in domestic space, social suspicion, and moral warning.

→ Household Yokai Index

Later Interpretations and Legacy

In later retellings and modern media, abura-sumashi is sometimes simplified into a grotesque yokai character. However, such portrayals often flatten its original complexity.

A historically grounded interpretation recognizes abura-sumashi as a product of urban life, regulated religion, and moral negotiation. It belongs to a class of yokai that critique society rather than simply frighten it.

Modern Cultural Interpretations

This modern reinterpretation visualizes Abura-sumashi as a yōtō — a cursed blade whose oil-like sheen symbolizes quiet extraction and incremental loss.

The blade represents theft without violence, translating folkloric anxiety into contemporary metaphor.

In modern interpretations, Abura-sumashi is often treated as a symbol of hidden consumption — the quiet theft of resources that communities depend on. Contemporary retellings sometimes shift the focus from “a strange little yōkai” to the social conditions that produce scarcity, suspicion, and scapegoats.

Psychologically, Abura-sumashi can be read as the discomfort of noticing what is taken in small amounts: minor betrayals, slow erosion of trust, or the fear that someone is benefiting while remaining unseen. The figure becomes less about overt evil and more about lingering social paranoia.

In some modern visual reinterpretations, Abura-sumashi manifests as a yōtō — a blade that gleams with a thin, oil-like sheen. It does not demand bloodshed; it “takes” by degrees, dulling resolve and slipping value away without a single dramatic moment. The sword embodies theft that is incremental, almost polite — and therefore harder to stop.

Abura-sumashi endures because what is stolen quietly is often noticed too late.

Modern Reinterpretation – Abura-sumashi as a Contemporary Yokai

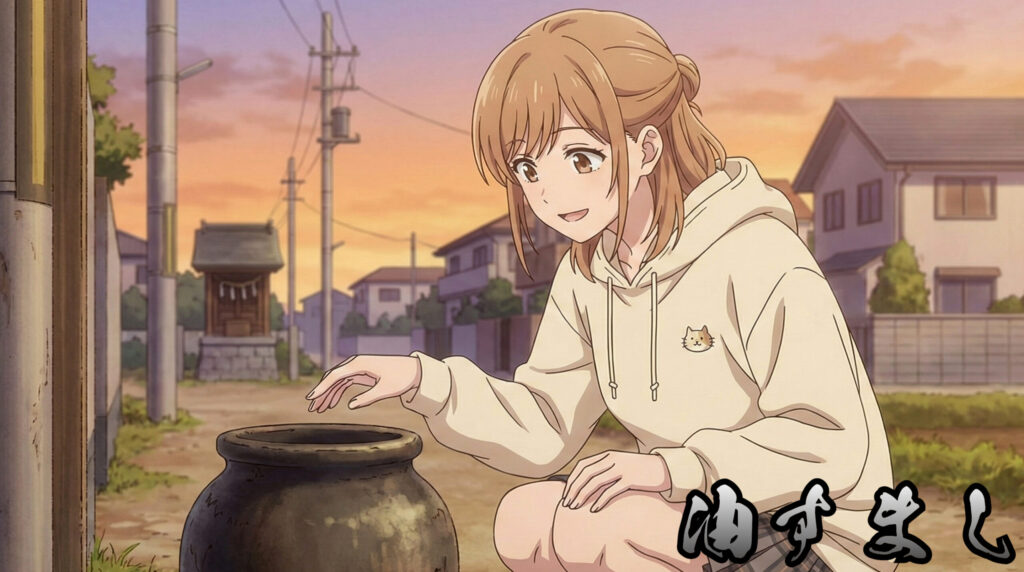

In this reinterpretation, Abura-sumashi is not portrayed as a grotesque mountain spirit, but as a quiet, approachable girl — a form deliberately chosen to mirror the yokai’s most dangerous attribute: familiarity.

Historically, Abura-sumashi disguised itself as a wandering monk, exploiting social trust to siphon oil from household stores. In modern society, the mechanisms of trust have changed, but their vulnerability remains. The “beautiful girl” in this reinterpretation functions as a contemporary analogue of that disguise — an embodiment of harmlessness that masks subtle extraction.

Her calm gaze and muted color palette represent the slow, almost invisible depletion of shared resources. She does not threaten. She persuades. She belongs. And through belonging, she takes.

In this visual form, Abura-sumashi becomes a metaphor for contemporary systems that drain value while presenting themselves as friendly, helpful, and legitimate. It is not an invader. It is a neighbor.

Musical Correspondence

The accompanying track translates this quiet predation into sound. Soft, restrained rhythms echo the steady loss of oil, while dim harmonic progressions mirror the yokai’s preference for gradual manipulation rather than overt force.

Repetitive motifs simulate depletion without rupture — value disappearing not through violence, but through routine. Muted timbres and filtered textures suggest comfort that slowly reveals instability beneath its surface.

Together, image and sound form a unified reinterpretation layer — not as an illustration of folklore, but as a contemporary folklore artifact in its own right.

It embodies the concept of belonging as a mechanism for unnoticed depletion in modern social systems.